"Cold, delicately as the dark snow, A fox’s nose touches twig, leaf; Two eyes serve a movement, that now And again now, and now, and now Sets neat prints into the snow … " ~ "The Thought Fox" by Ted Hughes

Is there a creature more cunning than the sly Fox? If we go by Slavic folklore, the Fox would have hoodwinked you many times over before you even got to say, “Wait a minute … ” Swift-footed and stealthy, the Fox never claimed it had a heart of gold to match its fur.

There’s no messing with the Sly Fox.

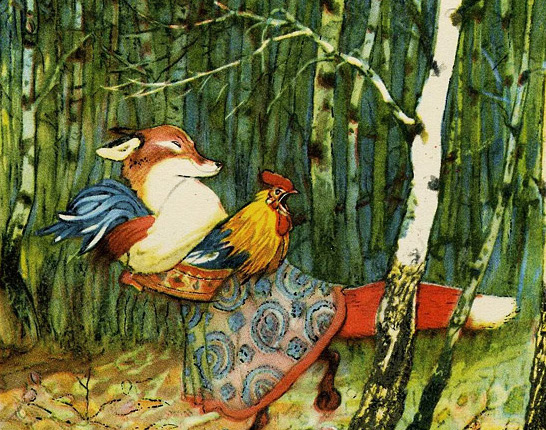

And so it was that where all others had failed, the Fox still manages to gobble up the runaway Little Round Bun (Kolobok), bamboozles the wolf who’s turned quite stupid with hunger (Sister Chanterelle and Brother Wolf), kidnaps the rooster (even if not for long) (Comb of Golden Hue), deludes the trusting bear into confessing gluttony (Fox Cheats the Bear out of His Christmas Fare), and woos the accidentally-brave governor cat for a husband (Liza & Catafay, and a charming video here). And of course, only a Fox could have told you that the grapes are sour (Aesop’s Fables, 4 BC)!

No, no, that ain’t an animal to cross, although no one said being clever was a bad thing. Especially when the cleverness wins over brute strength and plain malevolence. And perhaps, that’s why, we also forgive the Fox for its mischief so easily. The Fox never claimed to be a saint, my friends, and hypocrisy was never one of its sins:

Why encourage the notion of virtuous poverty? It’s only an excuse for zero charity. Hunger corrupts, and absolute hunger corrupts absolutely, or almost ... To survive we'd all turn thief … ~ from "Red Fox" by Margaret Atwood (Morning in the Burned House)

There’s also a certain gift of the gab, a wily charm, a playfulness about the Fox that’s quite charming and makes us willing to forgive the Fox and even endorse it. That old rogue.

So, what makes the Fox so cunning?

Is the Fox’s cunning only a thought trail from folklore, or does it run more biological? It seems that no animal is quite as successful as the Fox when it comes to evading hunter traps and fox hounds on the hunt. They also don’t live in packs, but can survive alone in almost every kind of habitat. They are also thrifty, stocking up food for emergency situations.

The Fox has excellent hearing and sense of smell, and its excellent “lurking” abilities help it to pounce unawares on its prey. It can dig holes under buildings and fencing to get to livestock such as chickens, rabbits and young lambs. While fox-hunting has been (mostly) banned, the Fox is still bred in farms for its precious fur, and for its ability to hunt down rodents and pests without harming the crops themselves. Its tail, that lovely bushy tail, is a balancing act, a warm cover in winters and also a signal “red flag” for other foxes.

When did we first begin to notice this wily creature?

Perhaps the oldest fables on the Fox’s cunning date back to more than 2000 years, to the Tales of Bidpai (also: Panchatantra or Tales of Kalila and Dimna). These are not as well known as The Arabian Nights, but had travelled as much from their point of origin in India before they were translated to English by Sir Thomas North. As per Doris Lessing in Time Bites, the Tales of Bidpai combine anecdotal lessons from the Buddhist beast-fables of Jataka Tales in India and the political treatise Arthasastra (3rd Cent. BC) by Kautiliya (quite similar to Machiavelli’s The Prince).

There are anthropomorphic versions of the Red Fox too, and as early as the Middle Ages, Reynard the Fox was getting into courtly intrigue and madcap adventures of outwitting other animals, particularly his uncle, the wolf Ysengrim. I found that there were several movies made out of the titular allegorical epic poetry of the 1100s.

For example, Renny the Fox (animation Le roman de Renart 2005) and The Fox and The Child (2007 movie with Kate Winslet’s VO). A 1930 vintage puppetry animation from Ladislas Starevich (a la Jim Henson’s puppetry) is also much acclaimed. And let me add that Disney’s completely campy Robin Hood (1973) and Zootopia (2016), the swindling fox in Pinocchio (Disney 1940), and The Fantastic Mr. Fox (1970) based on Roald Dahl’s book of the same name, also seem inspired by Reynard. I mean, who better to teach mayhem and manners than the Fox?

The Lore of Fox/ Human Shapeshifters

Not satisfied with tricking other animals, the Fox also resorts to shape-shifting to human form, to snare unsuspecting travellers. The Korean kumiho or gumiho, the Japanese/ Shinto kitsune, and the Chinese huli jing are all examples of this form of the Fox. They are usually nine-tailed, red or silver in colour, and possess magical “fox fire” as a weapon or treasure, and teeter wildly between wickedness (kill the human!) and humaneness (not all humans are bad!).

Although the shape-shifter fox mostly changes shape for carnivorous or avaricious reasons, sometimes it also ends up falling for or befriending the human. Several Asian TV dramas carry along these themes, including My Girlfriend is a Gumiho, Ten Miles of Peach Blossoms, Three Lives Three Worlds: The Pillow Book and Once Upon a Time in Ling Jian Mountain. All of these are well-made and highly recommended on the South East Asian roots of the lore.

There is also Janáček’s opera, The Cunning Little Vixen (1923), remade many times, including as a BBC 2003 animation, in which the vixen wishes to become a human woman.

Among books and comics, the shape-shifter fox finds mention in Kamisama Hajimemashita (I Became a God), a popular Japanese anime and manga about the kitsune familiar of a human-just-turned-god, and Tsumiko and the Fox by Forthright, a recent book phenomenon about a multi-tailed fox that has been enslaved to a human.

There are also tales about the kitsune pelt, which like a selkie’s pelt, aIso carries magical properties. Terri Wildling has extracted a lovely passage from mythographer Martin Shaw’s Scatterlings. In Seanan McGuire’s October Daye series, a much beloved Urban Fantasy series about a paranormal Private Investigator, a kitsune’s magical pelt is stolen by Luna Torquill to escape as a fox. (McGuire has also taken several motifs and names from the Reynard franchise, including “Tybalt”, the King of Cats; clearly she’s interested in the Fox lore too.)

Foxes and Cultural Symbolism

Foxes and events about the foxes have also become literary metaphors for something else.

For example, there is a curious symbolism between sunshowers and fox weddings, and there is too much literature across countries and cultures for it to be a passing fancy. I remember a poem by Harindranath Chattopadhyay back in school about The Fox’s Wedding. It was an odd wedding day, raining even though the sun was out.

“The cloud is dropping It’s rain in the sun, For the Fox’s wedding Has just begun.”

Another allegory is for the unpredictable, the spanner in the works, as Change comes home. I first heard of D.H. Lawrence’s novella The Fox in Time Bites. I thought it was a general critique by her of the books she had read/ enjoyed, but turns out it’s also the foreword to Lawrence’s book. Published in 1923, you can find it in the commons. In The Fox, a peasant woman becomes obsessed with a fox that’s stealing the precious chickens on the farm, but in classic Lawrence style, the Fox is a euphemism for something else.

Mr. Fox by Helen Oyeyemi is a psychedelic exploration of Bluebeard’s tale, in which the fox, by turns, becomes the muse, the lover, and the hunted. There are myriad interpretations possible, but one view is that the fox represents the feminine. The feminine has always been a subject of sacrifice, both in real life and in the literary devices that authors use to “fridge” women so as to give the hero an impetus on their quest.

The notion of equating foxes with the feminine is not new, although the Fox is a cousin to both dogs and wolves. In Ukrainian folk tales, the Wolf is Brother Wolf and the Fox is Sister Fox. In India too, the Fox is the Lomadi Mausi, or the gossipy aunt, who can’t resist meddling or gobbling up sweetmeats and is always up-to-no-good.

Thus, no matter the source, the Fox has become a popular motif in literature and culture, for the unpredictable, the wild, the feminine and the cunning.

The Evolution of Foxes

Over time, however, the Fox has lost some of its fabled cunning. The Farm Fox Experiment conducted in 1960s by Dmitri Belyaev and Lyudmila Trut (back when genetics was banned subject in Russia and so the scientists had to pretend they were breeding foxes for fur) showed a curious study in evolutionary biology. It appears that foxes that acted less fearful or feral towards humans could get better access to human-generated food, and unintentionally, a “natural selection” happened. The foxes (over several generations) developed smaller skulls and teeth, tail wagging, floppy ears (ahem, puppy dog look) and barks — and lost their musky fox smell. Here was unintentional domestication, and here did the Fox suffer fall from its grace. As Shinjiro Kurahara says in “A Footprint”:

“Long ago a fox ran along a clay river bank. After an interim of tens of thousands of years a footprint turned fossil remains. Looking at it, you'll see what the fox was thinking while running.”

Other Most Excellent Resources on the Fox:

Terri Wildling, A Skulk of Foxes

Fox News, at New Yorker

Cunning as a Fox, The Independent

Red Fox, National Geographic

(What, you’re slinking away? You’re a foxy one, hyuk hyuk.)